Bokator (Cambodia)

- Name of sport (game): Bokator or Lbokkator The term bokator translates as "pounding a lion" from the words bok meaning "to pound" and tor meaning "lion."

- Name in native language: ល្បុក្កតោ (Khmer)

- Place of practice (continent, state, nation):

Cambodia

- Village of Banteay Yuon and Sdao Chrum, Commune of Sya and Sre Sdok, District of Kandeang, Province of Pursat

- Village of Poral, Commune of Phnom Bat, District of Pornhealeu, Province of Kandal

- Urban area of Kampong Chhnang

- Village of Chres, Commune Rokakhnong, District of Daunkeo, Province of Takeo

- In the urban area and several districts of the province of Kampot

- In several districts of the Province of Svay Rieng

- Village of Tor Tea, Commune of Krabey Real, Province of Siem Reap

- Village of Thlok Chheuteal, Commune of Sopor Tep, District of Chhbarmon, Province of Kampong Speu

- Village of Khvet and Angdaung Reusey, Commune of Pong Ro, District of Roleabaea, Province of Kampong Chhang

- In several districts of the Province of Kampong Cham

- In Phnom Penh and in other provinces: Banteay Meanchey, Kandal, Preah Sihanouk, Koh Kong, Kratie, Oddor Meanchey Preah Vihear, Ratanakiri, Mondulkiri, Preyveng and Stung Treng. - History:

The ancient Khmer have practiced martial arts for 2000 years. Their country covered a significant part of Thailand, Laos and Vietnam.

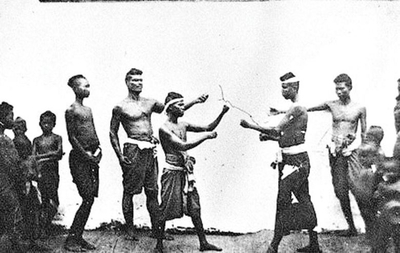

According to historians, the territory of the Khmer Empire once spanned mountain ranges, rivers, lakes and seas. Men lived there together with all kinds of animals such as tigers, lions and many other carnivores. To survive, the Khmer people strove to acquire the knowledge that would allow them to adapt to nature and defend themselves against all sorts of wild animals. Many archaeological digs across the country (Laang Spean, in the province of Battambang in 1964-1968, in 2009-2010-2012 in Memot, province of Kampong Cham, in 1962-1996 and then 2004 in the pagoda of Kumnou, province of Takeo, in 1999-2001 in Prohear, province of Prey Veng, in 2008-2010 in the village of Snay, in 2006-2009 in Sophy, in 2009-2010 in Kauktreas, and in the province of Banteay Meanchey in 2013) and the results of carbon dating on the objects found during these digs, point out that people began settling in these areas as early as the Neolithic: the inhabitants of this time were already capable of defending themselves and their communities; they possessed well-established beliefs including respect for the dead, to which they made offerings.The first traces of the Bokator, fighting scenes, strangulation techniques and strokes are found on Angkor reliefs, especially in Banteay Srey, in the tenth century they practiced martial arts of Indian origin (Sri Lanka or Kerala) called Maloyuth.

To survive, the Khmers passed down knowledge and tactics from generation to generation to protect their community and customs, which became traditions. This knowledge, which enabled them, in particular, to fight wild animals, was illustrated in sculptures on the walls of many temples such as Sambor Prei Kuk, Koh Ker, Baphuon, Bayon, Preah Khan, Banteay Chhmar, etc. Furthermore, a very great number of bas-reliefs in the temples of Angkor relating the legends of the Ramayana and the Mahabharata describe these combat techniques practiced in the actual lives of the people of the Khmer Empire. Still later, the frescos of the Kampong Tralach pagoda, erected in the early 20th century in the province of Kampong Chhnang, which can still be admired today, illustrate scenes of combat during traditional festivities in which combatants can be seen using their bare hands and feet, as well as sticks. The Khmer ancestors gave the name “Kun Lbokkator” to all these combat techniques.

- The term KUN describes the martial art of fighting, leaping, and confronting opponents according to the techniques specific to the warriors of the Khmer Empire (Venerable Chuon Nat, p. 137);

- The term LBOKKATOR refers to all combat techniques involving the half-kneeling position, neither too high nor too low. Kun Lbokkator is based on 12 positions. The combination of the various positions forms a specific combat technique. The term Kun Lbokkator is also present in Khmer literary works. According to the Khmer dictionary of the Venerable Chuon Nat, page 1,138, the term LBOKKATOR means a sort of short stick spanning the distance from elbow to hand used as a shield against the long staff of an opponent, or a combat technique using this short stick.

Bokator or L'bokator is a Khmer martial art that includes weapon techniques. One of the oldest existing combat systems in Cambodia, oral tradition indicates that the Bokator or its early version was a melee combat system used by the Angkor army 1700 years ago.

It is said that the boxer is the earliest systematized Khmer martial art. The name l’Bokkatao comes from Sanskrit, so it is thought to be native in India, like the Khmer culture. The pronunciation of the word "bok-ah-tau" comes from labokatao, which means "to hit the lion." This refers to a story that took place 2000 years ago. According to legend, the lion attacked the village, when the warrior, armed only with a knife, defeated the animal with his bare hands, killing animal with one strike at the knee.

Although the lion has cultural significance to Indochina, modern literature assumes that this was not the area of occurrence of the Asian lion, which currently lives in western India. Instead, large cats from Southeast Asia are an Indochina leopard and a tiger.

Indian culture and philosophy were the main features which had an influence on the culture of Angkor. All large Angkor buildings are dedicated to Hindu gods, especially Visnu and Shiva. Even today, practicing Bokator start each training session with respect for Brahma. Religious life was dominated by brahmanas, who also practiced sword fighting and empty hand techniques in India. The concept of animal-based techniques most likely appeared during the reign of the Angkor kings and during the simultaneous influence of Indian martial arts.

The reliefs at the base of the entrance pillars to Bayon, the state temple of Jayavarman VII, depict various Bokator techniques.

The Khmer Empire was huge, which meant that many martial arts were practiced on its territory. Hence the difference between Kun Khmer and Muay Thai is small. Style and strategy are slightly similar, although the rules are different. The use of elbows is preferred in Kun Khmer. Kun Khmer's warriors will be more looking for opportunities to strike an enemy to shorten the fight distance than wins for points.

Historically, Thai people have come to the present territory since the eleventh century, while the Khmers have been there since at least the first century AD with the kingdom of Funan. The Thai people were vassals of the Khmer Empire and worked as mercenaries until independence and victory over the Khmer in the fourteenth century. That is why they adopted the fighting techniques practiced at that time by Khmer and Mon (people practicing Burmese boxing) and appropriated Khmer culture along with the alphabet, dance, martial arts etc. Therefore, Cambodian boxing has many similarities to Thai boxing, because they both come from the same martial art.Bokator was the main basis of the martial arts used by Khmer ancestors when fighting their enemies. More recent research is showing that after the arrival of ammunition-firing canons, Bokator became a performing art or traditional leisure game, practiced during traditional festivities such as the Day of the Dead, the Buddhist Solidarity Festival (Kathin), the Khmer New Year, etc. A large number of Bokator fighting techniques have become essential building blocks for other forms of art and the performing arts: classic and folklore dances such as Toam Ming, Kantèrè, Bokleakh, Chhay Yam, Robaim Kbach Kun, and some combat scenes of Bassac theatre.

Although Cambodia was, during the centuries following the fall of Angkor, burdened by wars, Bokator remains and continues to survive within Khmer society. Master practicing in communities, certain pagoda venerables, instructors, supporters, national television networks, film producers, several Ministries of the Royal Cambodian Government and their provincial Departments, national and international sports clubs (in the United States, France and Canada in particular) are unanimous in their will to support and promote Bokator.

From the 17th century until 1953, Cambodia experienced many political turmoils. The element bearers and local authorities encouraged the defence movements in communities and formed militia groups. Bokator training and learning were organised for the villagers. The French Protectorate authority (1863-1953) even presented the best Bokator (stick or bare-handed combat) practitioners to the public during the French and Cambodian national festivities.

After 1953, the authorities continued to encourage Bokator learning and training, extending some of the combat techniques to other forms of sport such as modern Khmer boxing and traditional Khmer boxing and establishing national and international combat standards.

All the efforts and measures relating to bokator were entirely annihilated, the human resources decimated and documentation entirely destroyed by the genocidal Khmer Rouge regime. Some knowledge bearers that survived were able to reconstitute a partial knowledge of the element.

After the fall of the Khmer Rouge, the few masters who escaped pooled their knowledge to transmit it to new generations. However, the lack of opportunities and means significantly restricted transmission of their knowledge at a period when the war-ravaged country strived to rebuild itself.

The Ministry of Culture and Fine Arts of Cambodia conducted research to gather documentation on Bokator, inventorying 76 high-level practitioners and offering them the opportunity to transmit their knowledge. In collaboration with several television networks, Bokator performances and historical documentaries were broadcast.

The relevant public institutions also conducted research to document Bokator and form Bokator clubs. Competitions were organised at a national and international level. In 2010, Cambodia participated in the "Chungju World Martial Arts Festival" in South Korea.

Private partners, especially film and television programme producers started to show interest in Bokator to stage performances for audiences and make it part of their scenarios.

The Living Treasure system adopted in Cambodia did not include any Bokator masters amongst its 17 first nominations, completed by Royal Decree.

Since 2012, the Ministry of Culture and Fine Arts has been conducting an inventory of all masters, clubs, communities and potential pupils with a view to organising sustainable programmes to safeguard and transmit knowledge to future generations.

It may ,therefore, be observed that despite the efforts implemented, there is a true need for a precise, coordinated programme to safeguard this traditional martial art.

- Description:

Bokator is the general name for all Khmer martial arts: Kbach Kun Boran

Khmer - ក្បាច់គុនបូរាណ, which include:

1) Atmani Yuth – forms of fight with bare hands

In which you can distinguish:

- Kun Khmer (គុនខ្មែរ) – boxing

- Baok Chambab (បោកចំបាប់) - wrestling

The Atmani yuth boxing comes from Kun Daï. Kun Khmer, which means that Khmer art is a modern name meaning Khmer boxing, which will replace pradal serey.2) Ani Yuth –forms of fight with weapons

In which you can distinguish:

- Kbach Kun Dambong veign (ក្បាច់គុណដំបងវែង) – long stick fight

- L’Bokkatao (ល្បុក្កតោ) – fight with use of Kun Khel

- fight with the sword, short stick etc.

Currently in Cambodia there are many Bokator schools of martial arts and Kun Khmer, and their largest concentration is in Phnom Penh and several in Siem Reap.

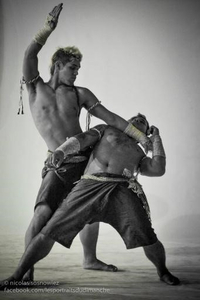

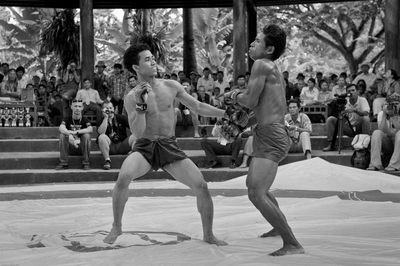

A common misunderstanding is that the Bokator refers to all Khmer martial arts, while in reality, he represents only one particular style. The competitor uses diverse punches of elbow and knee blows, shin kicks, dodges and ground floor fighting.

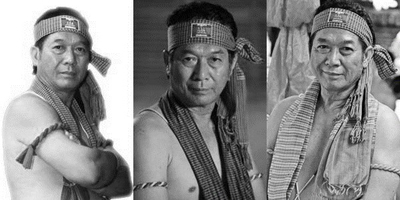

During the fight, Bokator champion still wears the clothes of ancient Khmer armies. The krama (scarf) is wrapped around the waist, moreover, a blue and red silk cord called "sangvar" is tied around the head and biceps. In the past, it was thought that cords had power and were put on to increase strength, although now they are only ceremonial.It should also be noted that the term Bokator is the master San Kim Sean’s choice (also the Cambodian sport ministery’s and the Cambodia Olympic Comitee‘s choice) to designate all traditional Khmer martial arts Kbach Kun boran Khmer (weapon techniques, supplies, etc.) except boxing (Kun Khmer) in commercial will and simplification. Because there are many martial arts in Cambodia, to simplify all this and facilitate expansion, the term Bokator (even Kun Bokator) was chosen.

The art contains 341 parts, which, like many other Asian martial arts, are based on observation of life in nature. For example, there are styles of horses, birds, eagles and cranes, each includes several techniques. Due to the visual similarity, the Bokator is often mistakenly described as a variant of modern kickboxing. Many forms are based on traditional animal styles, as well as simple practical fighting techniques. “Pradal serey” is a more condensed combat system that uses some basic techniques (white krama) to hit by using the elbow or knee and is without any animal styles.

Krama shows the advancement level of the warrior. The first level is white, followed by green, blue, red, brown and finally black. After completing the initial training, competitors wear black krama for at least another ten years. After the black krama there are also "dan", which in Khmer is called Tchouan, and a special krama, including a gold and a diamond. To reach the golden krama, you must be a real champion and do something great for the Bokator. This is certainly a time consuming and perhaps life-long undertaking: in the very part of martial arts without weapons, there are from 8,000 to 10,000 different techniques, of which only 1,000 need to be learned to reach the black krama. The practice includes the use of weapons, forms (tvear), animal techniques, standing combat, ground fighting and wrestling. Each of the first six contains tvear and the need to overmaster:

• Attack techniques, eg: feet, elbows, knees.

• Defense techniques.

• Animal movement techniques (Sath) and combat techniques (Maekun Veybok).

• A kun kru (ritual dance before the fight).Each level has its own difficulties, the higher the level, the more content. The duck and horse technique are white krama techniques necessary to obtain a green krama. The same applies to the techniques of Preah Noryeille (Vishnu), these are blue krama techniques to obtain a red krama.

All hard parts of the body are used in the Bokator: fists, feet, arms, head, knees, and elbows.

In Cambodia, there are regular competitions such as SEA GAMES in Phnom Penh.

The competitors compete in two categories:

- techniques

There are technical competitions in which the practitioner presents his tvear (kata,form), with bare hands or with a weapon (short stick, long stick or khel). The judges pay attention to the aesthetics of the movements and the quality of the exercises.

- fight

The fight takes place in a circle, in 5-minute rounds, and the players are accompanied by music (different from muay thai and kun khmer). All strokes are allowed except for strikes on the ground, neck, back and genitals. The referee quickly stops the fight when the players are on the ground if one is not moving. Of course, bites and sticking fingers in the eyes are also prohibited.

Fighters dance between each phase of the fight. There is an old legend which says that warriors who fought against animals performed a dance to enchant them and better neutralize. - Current status:

During the Pol Pot regime (1975–1979), those who practiced traditional Bokator art were either systematically exterminated by the Khmer Rouge, escaping as refugees, or stopped teaching and start hiding. After the Khmer Rouge regime, the Vietnamese occupation of Cambodia began and local martial arts were completely banned. San Kim Sean is often called the father of the modern Bokator and thanks to him this martial art has been largely preserved and spread. In Pol Pot's time, San Kim Sean had to flee Cambodia on charges of teaching hapkido and Bokator. In America, he began teaching hapkido at the local YMCA in Houston, Texas, and later moved to Long Beach, California. After living for some time in the United States and teaching and promoting hapkido, he discovered that no one had ever heard of a Bokator. He left the United States in 1992 and returned home to Cambodia to restore the Bokator tradition. In 2001, San Kim Sean moved back to Phnom Penh and after receiving permission from the new king, began teaching the local youth. In the same year, hoping to gather all the remaining living masters, he began to travel around the country looking for a Bokator lok kru or instructors who survived the regime. The few people he found were old, sixty to ninety years old, and tired of 30 years of oppression; many were afraid to teach art openly. After many persuasions and after the approval of the government, the old masters gave way and Sean successfully restored the memory of a Bokator to the people of Cambodia.

Contrary to popular belief, San Kim Sean is not the only labokatao master who survive. Others are Meas Sok, Meas Sarann, Ros Serey, Sorm Van Kin, Mao Khann and Savoeun Chet. The first national Bokator competition in history took place in Phnom Penh at the Olympic Stadium on September 26-29, 2006. 20 leading teams from nine regions took part in the competition.

In Europe, the Bokator is becoming more and more popular. Important people who popularizing this sport are:

François Moreau, like most practitioners in France he started with judo and then with Ju-Jitsu. He practiced boxing at the age of 17, kick-boxing and Full-contact. He later discovered Kung fu, perfecting himself in Sifu Gao Shikui in the style of a praying mantis: boxing Tang Lang. He obtained a black belt and an instructor diploma. At the same time, he practices Muay-Thai, Kun Khmer (Cambodian boxing) and Pancrace. He fights in each of these disciplines. He has the title of vice-champion of France 2004 and champion of France 2005.

Christophe Chiv, nicknamed Nak, began practicing martial arts from taekwondo at a small traditional club in Saint-Denis (France) at the age of six. He also practiced Shotokan karate, and at the age of 15 he decided to start boxing and kick-boxing. He appeared on the ring for the first time at the age of 16. He practices Kun Khmer (Cambodian boxing) and Bokator (Cambodian martial art).

- Importance (for practitioners, communities etc.):

Bokator is one of the key elements represented in Cambodia’s world heritage sites: the Angkor temples and the Temple of Preah Vihear. On an equal footing with the Royal Ballet and Sbek Thom (shadow theatre), Bokator is exclusively part of Cambodia’s intangible cultural heritage and is closely related to world heritage. While it may be said that the temples, which may be equated with the body, have been preserved, it is just as important to save the soul and spirit of this heritage. Bokator, carved into the bas-reliefs of the world heritage temples, deserves an emergency safeguarding programme in order to highlight the intangible aspects of world heritage.

Bokator is one of the most physical illustrations of the customs, traditions and knowledge of the everyday life of the ancient Khmers regarding defence against wild animals and invaders.

Bokator was part of the country’s national identity at the time of the Khmer Empire and also constitutes a key historical element in the fight to defend the Empire. This element can therefore not be ignored in studies and teachings about the history of Cambodia. Implementing an appropriate safeguarding programme is, therefore, an urgent matter before this element disappears or looses its initial form.

Nearly all bearers - Bokator masters - are generally more than 75 years old. Their health is very fragile and their memory not always very clear. Many of them are beginning to forget the important aspects of Bokator. Others are already dead and are soon to be followed. Some are mobility-challenged and are no longer capable of performing a full demonstration to their pupils.

As few young people show interest, there is a real shortage of human resources to renew Bokator. - Contacts:

Cambodia Kun Bokator Federation

Phnom Penh

+855 Phnom Pen, Cambodia

https://www.facebook.com/KunBokatorFederation/

Surviving Bokator

+1 416-616-4251

www.survivingbokator.com

https://www.facebook.com/bokatorfilm/Bokator Cambodia

https://www.facebook.com/Bokator-Cambodia-171150479572441/?eid=ARD4U4zL4CZwIi0xryAOdWq1zdoQux0qri9CqCkjID7XBPUMhhhoZyMmYUyRg_2aJ7AiAXx0_57TI8ORFederation Khmer Sak Yant

http://federationkhmersakyant.com/

(+855) 97 83 80 844 (Teven)

(+855) 86 200 253 (Sotun)Fédération Européenne de Bokator

https://www.facebook.com/federationeuropeennebokator/

Australian Bokator Association

+61 401 004 045

Seng 0401 004 045

Heng 0411 731 218

John 0400 121 036This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it. This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Iranian Bokator Association

https://www.facebook.com/IranianBokatorAssociation/

Bokator Academy

https://www.facebook.com/Bokator-Academy-Phnum-Phen-210787102360197/

+855 97 702 4523

Leak Rayong Bokator

https://www.facebook.com/KhmerMartialArt

Midle East

https://twitter.com/mekf_mebf

Bokator Fight

+855 10 904 074

https://www.facebook.com/Bokator-Fight-174109282649881/UP Bokator Club

https://www.facebook.com/BokatorPuthisastra/

#55, Street 180-184, Sangkat Boeung Raing, Khan Daun Penh

12000 Phnom Penh

+855 87 752 998

Bokator Morodok Khmer

https://www.facebook.com/bokatormorodok.khmer/

126 street 598,Toul Kork, Phnom Penh

Phnom Penh

+855 17 728 347

La Bokator A.K.A Khmer Martial Arts

Email:This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Phone: (562) 230-5731

Address: 1321 E Anaheim St, Long Beach, CA 90813

- Sources of information :

Books, articles:

Ang, C., La lutte et d'autres jeux de physique. Recueil des articles de presse sur la Culture khmère, No1., 2005-2006

An, C. H., Lbokkator et les arts du spectacle. Phnom Penh, 2012

Chuon, N., Dictionnaire khmer-khmer. Phnom Penh, 1967

Chey, V., Khmer traditional boxing. Southeast – Asian culture year 2004

Chuch, P., Fouilles archéologiques à Snay. Centre de recherche international du Japon, Yooshinori Yasuda, 2008

Daim, T., Les épisodes de la galerie intérieure du temple de Bayon. Mémoire de Licence. Faculté de l'archéologie. Phnom Penh, 2005

Heng, S., Forestier, H., Le site archeologique de Laâng Spean. Rapport sur la première fouille archéologique, 2009

Im, S., La vie du peuple khmer après l'époque angkorienne à travers les sculptures sur les bas-reliefs du temple de Bayon. Mémoire de Licence. Factulté de l'archéologie. Phnom Penh, 1995

Iv, P., Les épisodes de la galerie extérieure du temple de Bayon. Mémoire de Licence. Faculté de l'archéologie. Phnom Penh, 2004

Khiev, Ch., Seng, S., Le temple de Banteay Chhmar. Mémoire de Licence. Factulté de l'archéologie. Phnom Penh, 1997

Khing, H., La fable d'Angkor. Littérature et civilisation khmères. Librairie d'Angkor, 2006

Leclere, A., L'histoire du Cambodge. Paris, 1914

Meas, S., L'héritage des arts martiaux khmers. Phnom Penh. Vol. 1., 2011

Oreilly, D., A Compendium of Archaeological Research Undertaken in Cambodia. University of Sydney Australia, 2009

Nou, S., Rapport de la recherche sur les arts martiaux khmers. Département du Développement culturel. Ministère de la Culture et des Beaux-arts, 2007

Roath, S., La Boxe khmère, 2012

Sam, A., Preah Chan Korup. Institut bouddhique. Phnom Penh, 1833

San, K., Khmer Martial Arts-Boxkator History 2000 years. Angkorian Traditional Martial Art. Bokator Competition Rule. Phnom Penh, 2004-2008

Sok, Th., L'histoire des arts martiaux khmers. Département de la Culture et des Beaux-arts de la province de Kampong Chhnang, 2012

Taing, Rinith, The Kingdom’s oldest wrestling form grapples with fading interest, The Phnom Penh Post, 7 Apr. 2017, retrieved 21 Apr. 2017

Vanna, Ly, Khmer Traditional Wrestling, Leisure Cambodia, August 2002, retrieved April 21, 2017

Vogel, S., 2009. Aspect de la culture traditionnelle des Bunong du Mondulkiri. Phnom Penh.

WOMAU News, The World Martial Arts Union 2009 become a NGO in operational relation with UNESCO.

World Martial Arts Union (WOMAU) W.M.A.F Promotion Committees 2010.Articles (web):

http://federationkhmersakyant.com/bokator--khmer-martial-arts.html

http://blog.aseankorea.org/?p=4072

http://www.taipeitimes.com/News/editorials/archives/2007/10/14/2003383133

http://www.talesofasia.com/rs-99-bokator.htm

https://theculturetrip.com/asia/cambodia/articles/bokator-the-history-of-traditional-khmer-martial-arts/

https://www.khmertimeskh.com/506074/the-lady-is-a-bokator-fighter/

http://www.fullcontactmartialarts.org/bokator-khmer.html

https://www.scmp.com/lifestyle/article/2142056/ancient-martial-art-spawned-muay-thai-undergoes-rebirth-cambodia-thanks

http://www.leisurecambodia.com/news/detail.php?id=113

https://www.phnompenhpost.com/arts-culture/kingdoms-oldest-wrestling-form-grapples-fading-interest

http://www.rfi.fr/hebdo/20180406-surviving-bokator-cambodge-documentaire-art-martial-khmer-rougeVideo:

https://vimeo.com/284746421?fbclid=IwAR25qBLZePl1vasUqv3QmOcfXEyg_jUYbVTGs54R2znvBU1X84TR3aZQme8

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RalqHrCChWI

Martial Arts Odyssey: Bokator: The Khmer Martial Art Parts 1: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Gobc3zSjXZU

Martial Arts Odyssey: Bokator: The Khmer Martial Art Parts 2: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KBwvwThib5s - Gallery: