SAVING THE LEGACY: THE PREHISPANIC BALLGAME

Arturo Iván Sánchez Monroy

Archeologist from the National School of Anthropology and History from Mexico

Member of Mexican Federation of Traditional Sports and Games.

In recent years, the practice of a sport that has its origins more than 3000 years ago has caused interest in several groups of enthusiastic young people in Mexico; it is the ball game, today called Ulama.

Its main characteristic, which is at the same time its greatest attraction, is that it is played by hitting a rubber ball that ranges from 3 to 5 kg and in its most popular version, this hit is made exclusively with the hip (in the other two, people uses the forearm or a mallet) and some records such as ceramic figures found in the area of El Opeño, in the state of Nayarit, show that it was not an exclusive practice of men, but also women played it.

The beginnings of the Ulama date back, according to the most recent archaeological studies, to approximately 1650 BC, in the Paso de la Amada region in the Mexican state of Chiapas. There, archaeologists found the remains of what would be the first space built for their practice, the oldest court so far.

Another important discovery about the age of the game is the one made in 1988 in the Manatí region, in the state of Veracruz. There, along with some offerings, rubber balls were found with which the game is carried out, as well as other elements related to it. All this material was dated to 1100 BC, during the preclassic period of Mesoamerica.

The courts in which it was practiced had different shapes, since some have the shape of an "I", others the shape of a joined double "T"; on some occasions they were closed at all four ends while on others one or two of their edges were open. However, the most common pattern in them is the presence of a deck in the lower part, a slope with a variable inclination and height in the middle and another deck in the upper part.

It was during the Mayan apogee in the classical period that different figures began to appear on the upper part of the slopes, such as bird heads, which serve as markers and which will continue to be appreciated until the epiclassic period in courts such as that of Xochicalco in the state of Morelos. These markers later gave way to the rings, sculptures that were placed in the middle of the slopes and in their highest part. Many of them were decorated with zoomorphic and anthropomorphic figures, various symbols and calendar dates, and a few were simply plain.

The largest court that is registered today is the one located in Chichen Itzá, in the state of Yucatán. Its measurements are 120 by 30 meters. In contrast, the smallest field is located in Cantona, in the state of Puebla and measures 14 by 6 meters.

This game is recorded as something more than a simple sport, but as a very important ritual since in the various cultures that inhabited the Mesoamerican region (made up of Mexico and part of Central America) it is part of their mythology.

An example of this is found in the Mayan culture, who developed in the south of Mexico, Guatemala, Belize and Honduras, because according to the Popol Vuh, the main book that tells their myths of origin, the sun and the moon are two brothers Hun Hunahpú and Ixbalanqué, who earned their place in the sky after defeating the gods of the Mayan underworld one by one in various ball game encounters.

The Aztecs, correctly called Mexica, used it in different ways, either as part of a divinatory ritual dedicated to specific gods or ceremonies, in some occasions for recreational purposes and in some cases, as an alternative to avoid war (in those cases, the governor became one more player, making a greater effort because the game was inclined in favor of his cause), and it is precisely of this culture that we have more records, since the Spanish conquerors kept in their chronicles the record of all the activities they saw when they arrived in the new world, including the ball game.

It is from these writings that a few rules that applied to the game are known, such as the one that mentions that the game ends if any player managed to pass the hoop with the ball.

According to oral tradition, it is also from this culture that its current name comes from, since the Mexica called the game Tlachtli or Ulamaliztli; however, and over the years, this last name was gradually deformed and shortened to give way to the name by which it is known today: Ulama

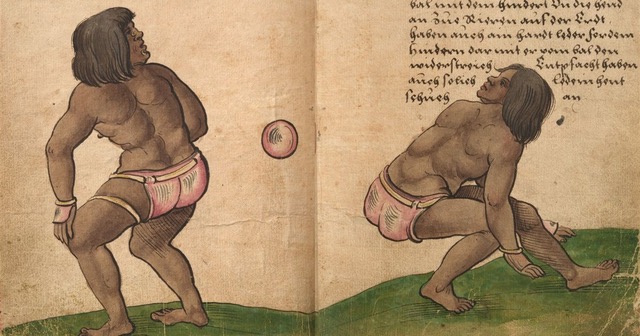

For the Spanish, the ball game was such a spectacular event that Hernán Cortés took a couple of players from the state of Tlaxcala in 1528 to demonstrate in front of King Charles V and Pope Clement VII. This moment was recorded by the artist Christoph Weiditz, who made an illustration of that presentation annexing his interpretation: “In this way the Indians play with the inflated ball, with their backside, without touching it with their hands, on the ground; they also have a hard leather on the butt, so that it receives the blow of the ball, they also wear a leather glove"

Unfortunately, its spectacularity was not enough to save it from the judgment of the Holy Inquisition, as it was consider a blasphemous exercise that only heretics practiced.

It was thus that after several years of tolerating its practice, it was banned by Fray Fray Juan de Torquemada a few years after the conquest in order to facilitate the work of evangelization of the natives, being destroyed the vast majority of the fields used to play it.

However, and in an effort to preserve it, the game continued to be played secretly from the friars and the Spaniards; its rules changed as well as the places where it was practiced. The large courts were exchanged for areas of land hidden among the planting bushes and it was no longer practiced in the big cities to be played in small towns far away from the conquerors. All this while in New Spain (as Mexico was called during the colonial era) the new religion, customs and traditions made the people forget, step by step, the practices of the past.

There is little information about the game in those centuries, and it was after the independence being consummated on 1821 when some news talked about that in the north of Mexico, more specifically in the region of Sinaloa, a game of pre-Hispanic reminiscences was played and was called Ulama.

It is well into the twentieth century when news of it are heard again, since in the mid-1930s the Mexican government again tried to ban it, this time considering it absorbing and dangerous, this being a low blow that would cause the game to be losing players until in the mid-80s it was close to disappearance due to lack of practitioners, to which the local government created programs that motivated its return to practice among the descendants of those players of yesteryear.

That is why in 2010, the document that declares Ulama as Cultural Patrimony of the State of Sinaloa was created, serving this to promote its practice again, this time in more regions.

Currently Ulama is already played in more than half of the states of Mexico and also in some regions of Guatemala, Honduras and Belize. The number of practitioners increases every day and for most of them, this is a great opportunity to connect with their roots, learn about their history and be part of social groups within their communities and live with other people outside their environment, all this without neglecting that this game It is also an excellent physical activity that encourages sports and healthy coexistence among its practitioners since, being in the process of growth, it also allows new players to have enough time to familiarize themselves with the rules and techniques and obtain a good competitive level.

At the end, and all of them seek a common goal, not only that the game does not disappear, but also to return the greatness and importance that it had more than 500 years ago.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Mc Kenzie Satterfield A., The assimilation of the marvelous other: Reading Christoph Weiditz’sTrachtenbuch (1529) as an ethnographic document, Department of Art and Art History, College of Visual and Performing Arts, University of South Florida, 2007

De la Garza Mercedes, El juego de pelota según las fuentes escritas, Arqueología Mexicana 44, pp. 50-53, 2000

Whittington E. Michael, The sport of life and death. The mesoamerican ballgame, Ed. Mint Museum of Art, 2002

Sahagún Fray Bernardino, Historia General de las cosas de la Nueva España, Ed. Porrúa, 1956