Gosse Pulling (Netherlands, Belgium, Germany)

- Name of sport (game): Goose pulling (also called gander pulling, goose riding, pulling the goose or goose neck tearing)

- Name in native language: Ganstrekken in the Netherlands, Gansrijden in Belgium, Gänsereiten in Germany

- Place of practice (continent, state, nation):

Netherlands, Belgium, Germany

- History:

Goose pulling (also called gander pulling, goose riding, pulling the goose or goose neck tearing) was a blood sport practiced in parts of the Netherlands, Belgium, England, and North America from the 17th to the 19th centuries. It originated in the 12th century in Spain and was spread around Europe by the Spanish Third.

In El Carpio de Tajo (Spain) goose pulling is practised on every July 25th to celebrate the liberation (Reconquista) from the Arabs in 1141. Later, during the dictatorship of Franco, the use of live geese was prohibited by a new animal protection law. Instead of geese, ribbons tied to sticks were used, which the riders had to insert into metal rings. When democracy returned to Spain, the use of geese was again allowed.

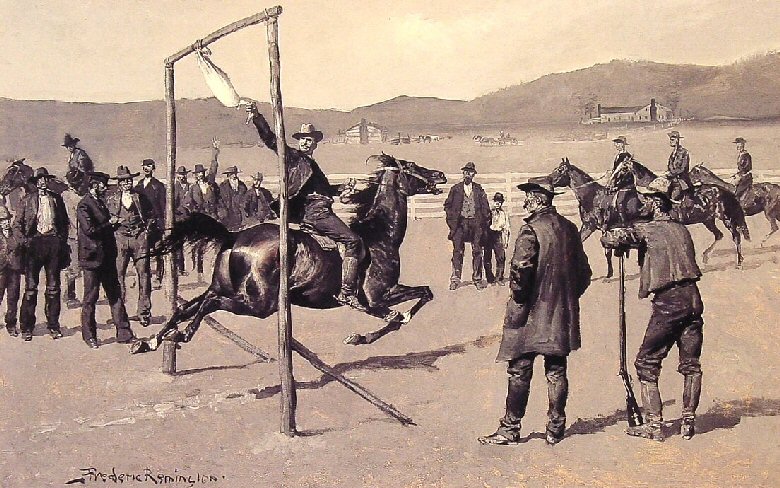

Goose pulling in 19th-century West Virginia, as depicted by Frederic Remington (source:https://www.wikiwand.com/en/Goose_pulling#/overview)Goose pulling is attested in the Netherlands as early as the start of the 17th century; the poet Gerbrand Adriaensz Bredero referred to it in his 1622 poem Boerengeselschap ("Company of Peasants"), describing how a party of peasants going to a goose-pulling contest near Amsterdam end up in a brutal brawl, leading to the lesson that it is best for townspeople to stay away from peasant pleasures.

Although the use of live geese was banned in the Netherlands in the 1920s, the practice still arouses some controversy. In 2008 the Dutch Party for Animals (PvdD) proposed that it should be banned; the organisers, Folk Verein Gawstrèkkers Beeg, rejected the proposal, pointing out that there was no question of cruelty to animals because the geese were already dead.Belgian goose pulling is accompanied by an elaborate set of customs. The rider who succeeds in pulling off the goose's head is "crowned" as the "king" for one year and given a crown and mantle. At the end of his "king year" the ruling king has to treat his "subjects" to a feast of beer, drinks, cigars and bread pudding or sausages held either at his home or at a local pub. The kings compete with each other to become the "emperor". Children participate as well; in 2008, the children's goose pulling tournament in Lillo near Antwerp was won by a 14-year-old who won 390 euros and a trip to the Plopsaland theme park.

In Wattenscheid (Germany) it is believed that the custom was brought by Spanish soldiers who were stationed in 1598 and 1599 during the Eighty Years' War and later in the Thirty Years' War. In some other places of Germany it was forbidden.

The sport appears to have been relatively uncommon in Britain, as all references are to it as a curiosity practiced somewhere else. The 1771 Philip Parsons locates it in "Northern parts of England" and assumes it is unknown in Newmarket in Southern England.

In a satirical letter to Punch in 1845 it is regarded as a barbarous practice known only to the bloodthirsty Spaniards, like bull-fighting.

The serious work Observations on the popular antiquities of Great Britain, of 1849, calls it "Goose-riding" and says it has been "practiced in Derbyshire within the memory of persons now living", and that the antiquary Francis Douce (1757–1834) had a friend who remembered it "when young" in Edinburgh in Scotland.

From these references it would appear to have died out in Britain by the end of the 18th century.The Dutch settlers of North America brought it to their colony of New Netherland and from there it was transmitted to English-speaking Americans. Goose-pulling was taken up by those at the lower levels in American society,[3] though it could attract the interest of all social strata. In the pre-Civil War South, slaves and whites competed alongside each other in goose-pulling contests watched by "all who walk in the fashionable circles."[13] Charles Grandison Parsons described the course of one such contest held in Milledgeville, Georgia in the 1850s (Parsons, Charles Grandison (1855). Inside view of slavery: or A tour among the planters. John P. Jewett and Co. pp. 136–7).

The prizes of a goose-pulling contest were trivial – often the dead bird itself, other times contributions from the audience or rounds of drinks. The main draw of such contests for the spectators was the betting on the competitors, sometimes for money or more often for alcoholic drinks. One contemporary observer commented that "the whoopin', and hollerin', and screamin', and bettin', and excitement, beats all; there ain't hardly no sport equal to it." Goose-pulling contests were often held on Shrove Tuesday and Easter Monday, with competitors "engaged in this sport not just for its excitement but also to prove they were "real men," physically strong, brave, competitive and willing to take risks."

Unlike some other contemporary blood sports, goose pulling was often frowned upon. In New Amsterdam (modern New York) in 1656, Director General Pieter Stuyvesant issued ordinances against goose pulling, calling it "unprofitable, heathenish and pernicious." Many contemporary writers professed disgust at the sport; an anonymous reviewer in the Southern Literary Messenger, writing in 1836, described goose pulling as "a piece of unprincipled barbarity not infrequently practised in the South and West." William Gilmore Simms described it as "one of those sports which a cunning devil has contrived to gratify a human beast. It appeals to his skill, his agility, and strength; and is therefore in some degree grateful to his pride; but, as it exercises these qualities at the expense of his humanity, it is only a medium by which his better qualities are employed as agents for his worser nature." (Simms, William Gilmore (1852). As good as a comedy: or, The Tennesseean's story. A. Hart. p. 115.)

The sport was challenging, as the oiling of the goose's neck made it difficult to retain a grip on it, and the bird's flailing made it difficult to target in the first place. Sometimes the organisers would add an extra element of difficulty; one writer describing an event in the American South witnessed "a [man], with a long whip in hand ... stationed on a stump, about two rods [10 m / 32 ft] from the gander, with orders to strike the horse of the puller as he passed by." The reaction of the startled horse would make it even more difficult for the puller to grab the goose as he went by.

Goose-pulling largely died out in the United States after the Civil War, though it was still occasionally practised in parts of the South as late as the 1870s; a local newspaper in Osceola, Arkansas reported of an 1870s picnic that "after eats, gander-pulling was engaged in. Mr. W.P. Hale succeeded in pulling in twain the gander's breathing apparatus, after which dancing was resumed."A variant called "rooster pulling" has survived in New Mexico for some time. A rooster was buried in the sand up to its neck, and riders would try to pull it up as they rode past. This was later done with bottles buried in the sand.

- Description:

The sport involved fastening a live goose with a well-greased head to a rope or pole that was stretched across a road. A man riding on horseback at a full gallop would attempt to grab the bird by the neck in order to pull the head off. Sometimes a live hare was substituted.

- Current status:

It is still practiced today, using a dead goose, in parts of Belgium and in Grevenbicht in the Netherlands as part of Shrove Tuesday and in some towns in Germany as part of the Shrove Monday celebrations. It is referred to as Ganstrekken in the Netherlands, Gansrijden in Belgium and Gänsereiten in Germany using a dead goose that has been humanely killed by a veterinarian.

- Sources of information :

Edward Brooke-Hitching. Fox Tossing, Octopus Wrestling, and Other Forgotten Sports, Simon and Schuster, 2015

John Brand, Sir Henry Ellis, Halliwell-Phillipps, James Orchard (1849). Observations on the popular antiquities of Great Britain: chiefly illustrating the origin of our vulgar and provincial customs, ceremonies, and superstitions, Volume 2. London: Bohn, 1849

Elizabeth Hafkin Pleck, Celebrating the family: ethnicity, consumer culture, and family rituals. Harvard University Press, 2000Video:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=heZVmRXSP9s

https://www.thesun.co.uk/news/4104903/goose-pulling-tradition-video/ - Gallery: