- Name of sport (game): Palapala

- Place of practice (continent, state, nation):

Cameroon

- Sources of information :

- Name of sport (game): Savika

- Place of practice (continent, state, nation):

Madagascar

- Description:

Traditional Sport Betsileo born in Amoron’i Mania (Ambositra), the Savika is a kind of bullfight which consists in fighting with bare hands against a zebu, clinging to the bump or the horns of the animal. The goal is not to hurt or kill the animal, but to prove his own strength.

- Current status:

At present, the Savika becomes popular and is one of the main attractions at the celebration of Easter and Pentecost.

- Importance (for practitioners, communities etc.):

It is a rite of passage that must do a young man to be accepted as a man responsible in the community.

Savika technique is transmitted from father to son. The zebu holds a symbolic place in the Malagasy rural society; it is in all the events: funerals, “famadihana” (exhumation) and other traditional rituals.

It is also essential companion during field work: trampling rice, pulling plows. The father entrusts to his son the care of guarding the herd, he must observe the behaviour of each animal and get to know it. The day he shall pass to Savika, he must prove that he is a man now, and as such capable of assuming its responsibilities within the family and community. - Sources of information :

Articles:

Ernest Ratsimbazafy, Construction identitaire à travers deux pratiques corporelles. Construction identitaire à travers le savika et le moraingy, Saarbrücken, Presses académiques francophones, 2015, 340 p.

Fabrice Folio, Serge Bouchet, « Promotion du tourisme culturel par la mise en tourisme du savika », in Océan Indien, enjeux patrimoniaux et touristiques : actes du Grand séminaire de l'océan Indien 2014, Université de la Réunion, 2014, 224 p.Video:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FMHZ3Bsa6cc

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ahDPfu7E7yw - Gallery:

- Name of sport (game): Sebekkah or Sebekkha or Sebek-khah

- Place of practice (continent, state, nation):

Egypt

- Name of sport (game): Shirra

- Place of practice (continent, state, nation):

Marocco

- History:

It's one of the oldest sports in Morocco, it brings together the different Tributes of a given region around a ball of wool or dome (الدوم) and wooden sticks.

This game is somewhat similar to Field Hockey. - Description:

The match takes place in two halves of 10 minutes each 5 players for each team The team that scores the most goals is declared the winner.

- Name of sport (game): Sorro

- Place of practice (continent, state, nation):

Niger

- Description:

Sorro Wrestling is a traditional sport of Niger (a country in Western Africa), originated and is currently practiced only in that country. The sport is a traditional style of wrestling in which all of the moves take place with both wrestlers on their feet. The objective of a match is to force any part of the opponent's body onto the ground, except the feet. Techniques such as tripping and holding the opponent by their legs are allowed in the sport.

Bouts take place in a large circular field with no boundaries and has a loose desert sand surface. There are no time limits and no out-of-bounds rules are there in the sport and the fight ends only by an outright winner.

The sport has no major scheduled events and bouts are usually conducted as a part of major festivals and occasions.https://sportsmatik.com/sports-corner/sports-know-how/sorro-wrestling/?tab=info&

- Sources of information :

Video:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oBCvQ66y8vMSource of photos used in this article and gallery:

https://sportsmatik.com/sports-corner/sports-know-how/sorro-wrestling/?tab=info& - Gallery:

- Name of sport (game): Ta kurt om el mahag

- Name in native language: Ta kurt om el mahag

- Place of practice (continent, state, nation):

Libya

Ta kurt om el mahag (the ball of the pilgrim’s mother) or, more commonly, Om el mahag (the pilgrim’s mother). Berber Baseball according to the statement of the Berbers of Jadum, is played only by the Berber tribes of the Gebel Nefusa.

- History:

Ta kurt om el mahag literally translates to “the ball of the pilgrim’s mother.” This game was discovered in the 1930s in a remote village in Libya, where the Berber tribesmen lived. It is said to have very similar rules and goals with baseball.

- Description:

Source: https://ourgame.mlblogs.com/rural-ritual-games-in-libya-berber-baseball-and-shinny-d17cf72c8ed9

The playing field consists of a level space without special boundaries other than those designated by home and one other base. In a shady spot in the middle of one side, a home base consisting of a rectangle about twelve feet in length is marked by stone or other signposts at its external limits. In front of the home base, some seventy to ninety feet away, a running base, called El Mahag, is marked. The game uses only one base like American “One O’ Cat.”

The game is played by two teams of equal numbers, each under a captain (sciek). The players choose two captains. Then the other men distribute themselves by couples and a man is assigned from every couple to each captain by chance. The number of players may vary from three to twenty on each side, but the usual number is six. The batting team (A) strikes the ball in batting order with a bat, sending it as far off as possible, so that the other members of the team may have time to run from home to the mahag and, if possible, back again. The men of the fielding team (B) try to prevent this by catching the ball as it flies, or by picking it up from the ground and throwing it to hit a member of the batting team as he runs from the gate to the mahag or back. When a team bats, it is called “marksmen” (darraba), and when it fields it is called “hunters” (fajadah).

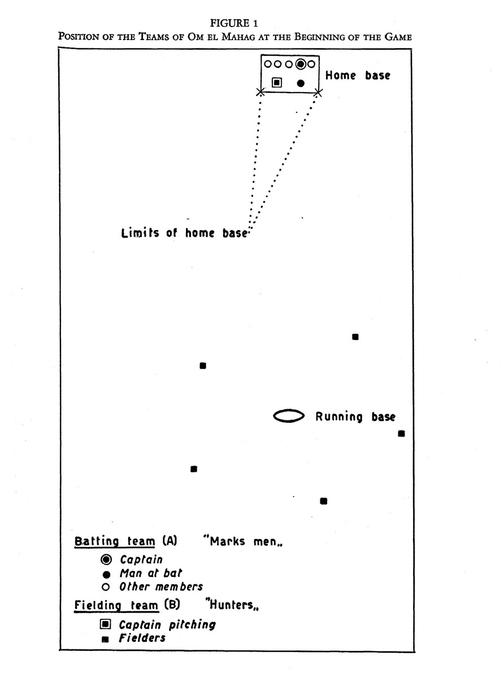

Lots are drawn at the beginning of the game to see which of the two teams bats first.Figure 1 shows the arrangement of the teams when the game starts.

Source: https://www.okayafrica.com/7-traditional-african-sports-olympics/

The batting team stands in full strength along the homebase; the batter in front, bat in hand, is faced at a distance of six to eight feet by the captain of the catching team who pitches the ball for his opponent to strike on the fly. The distance between pitcher and batter is such that the batter with outstretched arm can touch with the end of his bat the ball which the pitcher also holds at arm’s length. The mode of pitching makes it easy for the batter to hit the ball as it does not seem to be part of the game to strike out the batter. Before any batting is begun, the pitcher and the batter take the right distance and throw the ball back and forth several times, to make it easy for the batter to hit the ball. No catcher is used.

The leather covered ball is the size of the American baseball, but is not so hard. The bat is an olive branch which has been slightly curved by exposure to the heat of a fire, followed by slow drying. It is about three feet in length, somewhat flattened to about three fingers broad on the striking end.

In the batting order, the best batters are generally kept for the last and the captain ends the list of his team. The ball is always pitched by the captain of the fielding team. At first each member of the batting team is entitled to two strikes, the captain to three. When a batter misses all the strikes to which he is entitled, he withdraws to a corner, near one of the stones marking the limits of the home base, and hands the bat to the next man. He is then said to be “rotten” or to be set aside to “grow mouldy.” Should all the batters miss all the strikes to which they are entitled, the inning would be lost by the batting team (A), and the fielding team (B) goes to bat. It is, however, very unusual for all to miss. Like One O’Cat, no account of score is kept. The fun lies in keeping the bat as long as possible. As a matter of fact, a distinct advantage accrues to the batting team, as the members have much time to stand quiet in the shade, while the men in the field have to stand or run in the sun.

As soon as the ball is hit, all members of the batting team who have already batted (including also the “rotten” ones) run to the mahag. Sliding to the mahag is usual, as sliding into base in American Baseball. However, since the Berber merely has to avoid being hit by the ball and does not have to be touched by a baseman as in Baseball, he often slides and rolls into the mahag sideways. On reaching the mahag the men of the batting team generally stop, shouting out “mahag, mahag”; if, however, they have time, they run back to the home base, shouting all the time and mocking their opponents. The player who succeeds in running to the mahag and back is entitled, if he has not yet batted, to one more strike. Then a member of the batting team is entitled to three strikes and the captain to four. The batter does not always follow his comrades in making the run to the mahag. He must do so after the last strike to which he is entitled, but after other strikes he only runs when the blow he has given has been a very heavy one so that he thinks he has hit a “home run.”

Meantime the fielding team (B) has placed its men back or aside of the mahag or running base. They come nearer or spread out according to the strength of the batter. They try to catch the ball as it flies past or else pick it up from the ground as swiftly as possible. If the ball is caught in the air the inning finishes with the victory to the fielding team (B), which now goes to bat. If the ball is picked up, the picker tries to hit one of his opponents who is running to or from the mahag. If he succeeds, the fielding team run immediately to the home base, because a member of the batting team (A) may pick up the ball and hit one of the fielders with it. If he does so and saves himself on the mahag or on the home base, the earlier advantage to the fielding team (B) is forfeited. It is easier to reach the mahag than to make a home run in one hit. It generally requires two strikes for reaching the mahag and returning home. This explains why the batter only runs to the mahag either after the last hit to which he is entitled, or, in exceptional cases, after he has struck what he thinks is a home run. Sometimes the batter is mistaken in his estimate, so that, after having reached the mahag, he has insufficient time to return to home base. Then, if the batter is not the captain of the team, the next member of the batting team (A), takes the bat. If the batter is the captain, who always bats last, there is no following man to bat. In that circumstance, the captain of the batting team (A) takes a three-step lead from the mahag, and tries to steal home while a man of the fielding team (B), tries to hit him. If the captain of the batting team (A) is not touched by the ball, the inning is continued for the batting team (A), and the batting order begins again. If, on the contrary, the captain of the batting team (A) is touched by the ball, and no successful retaliation is made, as described above, the side is out and the fielding team (B) goes to bat.

The men do not use mitts, but catch the ball in their bare hands.

When a fielded ball is thrown and hits one of the members of the batting team (A), and the advantage is not forfeited, as above, the whole of the field team (B) gathers round the mahag, except the captain who goes to bat. The opposing team (A) then goes to the field and its captain pitches. Should the B captain who now has to hit the ball, miss it thrice, then the advantage accruing to the B team now gathered round the mahag is forfeited. In that case, the B team retires to the field while the A bats again. But should the B captain hit a fair ball, which is uncaught, his men, gathered round the mahag, try to run home. If they succeed without being hit by the ball which their opponents have picked up, the former fielding team (B) becomes the batting team. Should they not succeed in this, their advantage is forfeited and the teams resume their respective position.If the pitcher, having the ball in his hand, or catching or picking it up in the neighborhood of the home base, sees one of the men of the batting team outside the home base and the mahag, he can throw the ball and, if he succeeds in touching the man off base and no successful retaliation is made, the inning is for the field team which now goes to bat.

When playing at ball, whether Om el mahag or Ta kurt na rrod, the Berbers take off their barracans. Does this have a ritual significance or is it merely a concession to the freedom of movements necessary to the play? The last explanation seems obvious; but it is advisable to remark that the Berbers otherwise never remove their barracans. It may be interesting also to note that, in the formation of the teams, words are used that have no meaning for the Berbers of today. Probably they represent ancient vestigial words of which only the sound is remembered. To the possible ritual significance of the game I shall return later.Thus Om el mahag substantially resembles American Baseball. In both are found two opposing teams, each led by a captain; a base, the touching of which makes the player safe; the catching of the ball in mid-air; the throwing of the ball, by the men of the fielding team, when picked up from the ground, or by the pitcher, at the opponents who are not at the base. Innings, forced runs, base stealing, and most of the other key situations in American baseball are also found. The objects with which the game is played are similar, the ball and bat. The tasks assigned the two teams are fundamentally the same. Baseball is, in some respects, much more elaborate, but this, as is known, is due to relatively recent regulations. The chief differences from the structural point of view are the presence, in Baseball, of the catcher, who is lacking in Om el mahag, and the use of three bases — besides the home plate — instead of one. More important are the functional differences which make Baseball much more complicated and difficult to play, more violent and more strictly regulated than Om el mahag. Essential among these differences are the importance which pitching the ball has in Baseball, the effort to make it difficult for the batter to hit the ball, the consequent importance of the pitcher, and the fact that his function is independent of that of the captain of the team, and also, on the other hand, the difficulty of the task assigned to the batter, increased by the round shape of the bat. The greater violence of the game entails the need of masks, mitts and protectors, and the presence of umpires.

It should however be noted that at one time there was no umpire and no masks, mitts or protectors. And in many other particulars the old game of Baseball, before the introduction of the rules a century ago, was much more like Om el mahag. The bat was flat as in that game, no special tricks were used in throwing the ball so as to make it more difficult for the batter to strike it. The batter could hit the ball twice without running to the base; he was only required to run after the third hit. On the other hand, Om el mahag is complicated by the principle of retaliation which is not generally found in sand-lot and early Baseball.How are these similarities to be explained? Three suppositions seem possible. The game may have been borrowed by one people from another. This hypothesis is not, however, easily acceptable. It is difficult to see how an American or an Anglo-Saxon can have imported the game from the Berbers of the Gebel Nefusa. It is no less difficult to suppose that the Berbers, of the Gebel Nefusa have in past centuries imported their game from America or Great Britain, The supposition of independent origin and the convergence of the two games also seems difficult to accept, in view of the marked and detailed similarities between the two complex games. If the games were simple they could more easily have an independent origin.

- Sources of information :

The information contained in the article comes from the following sources:

https://www.okayafrica.com/7-traditional-african-sports-olympics/

https://luxafrique.net/3-ancient-sports-found-africa/

- Name of sport (game): Tahtib

- Name in native language: تحطيب taḥṭīb (egyptian arabic); تحطيب - لعبة العصا originally named fan a'nazaha wa-tahtib ("the art of being straight and honest through the use of stick"); the word 'Tahtib' comes from 'Hatab' which means 'wooden stick'.

- Place of practice (continent, state, nation):

Egypt

Although sport is practiced throughout the Nile Valley in Egypt, it is especially concentrated in Upper Egypt in the governorates of Minya, Assiout, Sohag, Qena, Luxor and Aswan. Less often in the Delta region, in the Sharkiya Governorate, this tradition is primarily maintained especially in the countryside. In addition, in large cities such as Cairo and Alexandria, Tahtib practice is associated with the concentration of the Saeedy community (rural population of Upper Egypt). Tahtib is practised in desert areas by inhabitants of Bedouin communities.

However, Tahtib cultivation is not limited to Upper Egypt communities, because the Tahtib tradition has been adopted by other rural communities living in Delta. It happened as a result of a large migration of people from Upper Egypt who, practicing Tahtib, disseminated this sport, treating it as an important element of their cultural heritage, people wanted to preserve elements of their cultural identity. - History:

For many centuries, the stick has a special role in Egyptian social life, especially in rural life, because it accompanied with fallahs (the peasants) in their daily lives and is a sign of masculinity. The stick being the main tool of tahtib, the stick was a tool that accompanied the man since he inhabited the earth, so it was initially a supporting tool for him to carry wherever he went, then developed to a longer hand that he used to pick up the fruits far from his reach, or turned into a third foot that helps him to move.

Stick then developed to be a major tool in cattle grazing, to become a symbol of the shepherd's authority over his own herd. With with the escalation of human conflict, the stick became a weapon used in self-defense against threats.

The name, tahtib, is derived from the Arabic name of branches of dry trees (Hatab).

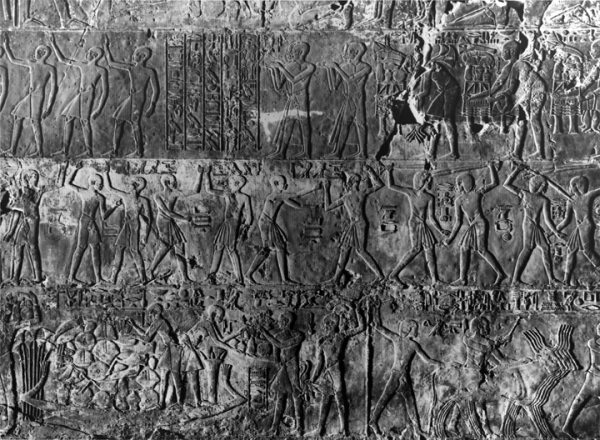

Tahtib is an original martial art using a stick,it has been known since the fifth Egyptian dynasty of King Sahourêh (2600 BC). The oldest signs of Tahtib were discovered in the figures from the archaeological stand of Abusir, a vast necropolis from the Old Kingdom period, located in the southwest suburbs of Cairo. Some reliefs of the Sahure Pyramid (V Dynasty, about 2500 BC), as well as paintings and signatures, are extremely accurate, depicting what appears to be military training with a stick. Tahtib, archery and wrestling were then mandatory elements of training soldiers. Engravings at the Abusir necropolis showing scenes of archery, wrestling, and stick fighting.

Engravings at the Abusir necropolis showing scenes of archery, wrestling, and stick fighting.

In three of the 35 tombs of the Beni Hassan necropolis (XI-XII dynasties, 1900–1700 BC), drawings of Tahtib scenes can be found near the city of Minya. Similar images can be seen at the archaeological stand of Tell el Amarna (XVIII Dynasty, 1350 BC), about 60 km from the south of Minya.

Tahtib is considered a martial art by using a stick to achieve the physical and mental perfection.

The art of tahtib, through its technical and rhythmic means that has evolved throughout its very long history, brings positive and consistent energy for both competitors and the audience as well.

The art of tahtib convey huge contributive potentials at the social and cultural levels in Egypt and abroad.

With the dawn of ancient civilizations, the ancient Egyptians invented the rules and origins of this sport and took great interest in it, as tahtib was not specific to a certain social group, and the ancient Egyptian artists engraved it on many walls of ancient pharaonic cemeteries and temples. In Giza governorate, inscriptions were found that belonged to King Sahoo Ra II of the Fifth Dynasty, which included symbols of tahtib. On the other hand, tahtib symbols appears as a ceremonial art in the era of the modern state 1500 - 1000 BC on the archaeological walls of the regions of Luxor and Saqqara, and archaeological inscriptions were also found in Minya Governorate, and that was during the reign of the eleventh and twelfth dynasties in the Temple of Medinat Habu, which the king Ramesses III built in the twentieth dynasty of the era of the modern state 1183-1152 BC, also found symbols depecting men playing with sticks in "Khro AiF" cemetery in the tombs of the nobles in Al Asasef, the western mainland in Luxor.

Tahtib in the Roman era:

It has been mentioned in primitive Christian literature that tahtib was practiced for entertainment and a form of folk art appears on holidays and weddings.

Tahtib in the Islamic era:

This sport was not limited to the Pharaonic era, but we find it in the Islamic era depicted in a Mamluk manuscript for equestrian sports dating back to the ninth Hijri century (15th century), preserved in the Museum of Islamic Art in Cairo with record number (18019 -18021). This manuscript has five pictures, three of them in The Museum of Islamic Art and two in the Sharif Sabri collection and photographs and they are depicting men playing with sticks, either standing - on their feet - or on horseback.

Also, "the stick" and "stick play" have been mentioned in the Holy Qur’an and the prophet Muhammad's narrations many times.

Today, this sport is perceived more as an artistic event than a sport competition, which expresses the attitude and skills of the body, strengthened by music played by folk musicians using traditional instruments derbouka / tabl (drum), mizmar (oboe).

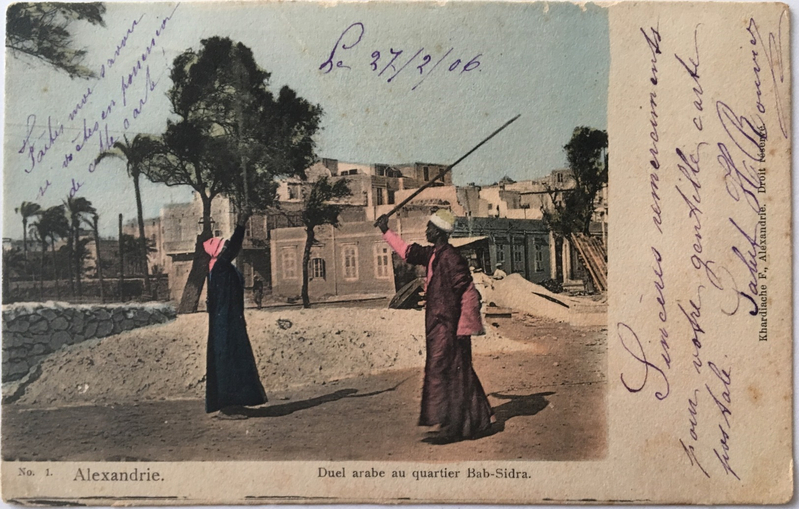

Tahtib au quartier Bab - Sidra. Alexandrie 1906 - Description:

Although Tahtib is a fight between two people, the event is a collective event in which players, musicians and the audience is gathered in a circle participate. Dance is used as an introductory phase and is a ritual of harmony. Each player holds the stick as a tool used for this duel. The stick used in Tahtib is about four feet long (about 130 cm) and is called asa, asaya, assaya, nabboot or nabut. The wood is oiled to prevent drying. The stick is held at one end. Some teachers recommend placing the thumb along the stick. The wrist remains flexible in rotation and is stiffened when stroke. The left hand moves on the stick to various defensive positions or attacks.

The duel begins with the rivals picking up the stick as a sign to start the fight, and then greeting each other. Each rival then ritually performs el-mussalpha. Competition begins only when rivals grab the sticks with both hands and start the fight. The winner is the one who touches the body of his rival with a stick. During the competition, everyone tries to move with a stick in such a way as to touch the body of the rival, and at the same time defends against touching the rival with the stick, mainly the head and upper body.

Spectators not only cheer but can end the competition if the rules are exceeded by one of the competitors.Tahtib has certain rules and promotes a number of values such as chivalry, strength, pride and harmony. Therefore, this sport is a source of entertainment, joy and pleasure during various celebrations.

Currently, Tahtib is a stick competition that lasts about a minute. Competition is in accordance with the rules, particularly it is important to:

1. Full mutual respect,

2. Full control.

Sheikh (judge) is responsible for the course of the competition; his decisions are definitive, especially when he witnesses hostility. Then he intervenes, sending away the perpetrator and calls for a new participant. Such intervention is called Al Qatea.

Tahtib skills are passed through training and combat simulation in which older people teach children at the age of 10. They begin with the rules and ethics, followed by stick and self-defense techniques, ending with the skills necessary to achieve advanced Tahtib techniques. Elders are happy to share their personal experience. It is important not only courage, strength, agility or cunning but also respect for the Tahtib tradition.

Practices with the Egyptian stick:

● Face to face, each person lifts the stick up. The wrist that holds the stick is turned inward, the stick is slightly inclined laterally to protect the face.

● Together, the partners are turning the stick over their heads, almost touching. This is done 4 times.

● Hitting with the sticks 4 times. Hitting in medium force, not more.

● Reversing the figure eight and doing the same as above - 4 times.

● Neutralizing body movement, walking normally, the same movements for the arms in one direction then the other. Reversal of direction of movement of the body. 4 times.

The principle is to touch, to touch the head or a body part. The head is decisive. It is forbidden to hit the hand, arm and shoulder.Tahtib, in addition to its defensive function, has been still practiced as entertainment, generally associated with various ceremonies such as marriage, return of the pilgrims and Mulid (feast of saints). The dance form of Tahtib was originally performed by men, but later women also began to participate in the performances, either dressing up as men and imitating them or in the form of a dance called ra's el assaya (dance stick).

- Current status:

The art of tahtib is currently practiced in various ways:

The first way: It is practiced as a sport and technique for self-defense.

The second way: It is practiced as a traditional popular game.

Third way: It is practiced as a show dance with the stick, and it is worth noting that the three types are also engraved on the walls of pharaonic temples and tombs.Tahtib is practiced by men from different social classes and age-group, starting at the age of 10, often continuing up to the age of 80. Many of them play an important role in promoting and protecting Tahtib, teaching the principles and skills of using the stick, their relatives, neighbours and everyone who is interested in it. They are happy to participate in various celebrations, presenting this sport. They also organize competitions to encourage experienced players, but also to introduce new ones, get to know different techniques and skills, trying to exchange and transfer knowledge. In addition, when Mulid is organized (even five nights), they take the opportunity to invite players from other regions.

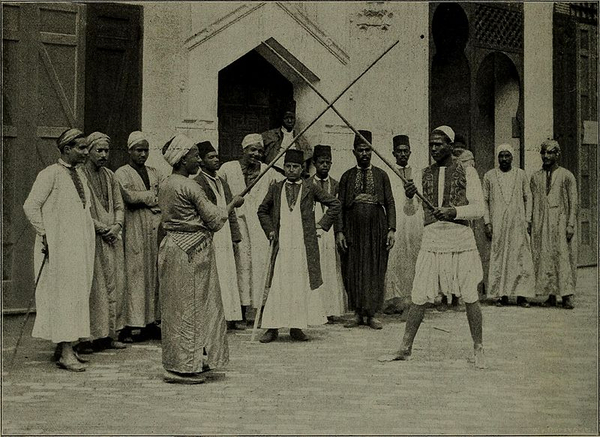

Staff Play in Cairo Street, World's Columbian Exposition (1893 Chicago, Ill.)

Staff Play in Cairo Street, World's Columbian Exposition (1893 Chicago, Ill.)The Egyptian government continues to play an important role in protecting this sport, both through education and practice. The Higher Institute of Folk Art (affiliated at the Art Academy of the Egyptian Ministry of Culture) lists Tahtib among popular Egyptian games and offers courses on how to learn it. A post-graduate Tahtib program is also available for interested institute students. In addition, the Ballet Institute encourages graduates to study Tahtib as an inspiration for choreography. The General Authority for Cultural Palaces promotes the creation of Tahtib groups and also organizes the annual Tahtib festival in Luxor. The Ministry of Sport promotes Tahtib activities in clubs and youth groups in all Egyptian governorates.

This martial art was inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage List as the intangible cultural heritage of Egypt in 2016. - Importance (for practitioners, communities etc.):

Tahtib engages both the player and the audience. An important element of this sport is respect for the elderly and for the weak. Tahtib is a practice, that strengthens family ties and good social relations because it is considered an important element of joint festivities. Practicing Tahtib gives young people a sense of responsibility. Strengthens team spirit between players of the same origin. It is an expression of the identity of those who practice this sport.

Its function has a social and festive dimension because people usually find Tahtib in social situations at various stages of life, such as marriages, local festivities or religious ceremonies. At the individual level, Tahtib practitioners seek self-esteem, respect for their community, and many other qualities that define him as a defender of their culture, community, and family. The Tahtib player is seen in the eyes of many as the hero of legendary folk tales. Rural communities play an important role in preserving Tahtib, especially thanks to their commitment to practicing and improving this sport, as well as their enthusiasm in passing it on to their children. Throughout its history, Tahtib has been of interest to communities that have regularly organized informal shows. Currently, Tahtib is the subject of many associations founded to protect this sport and to pass it on from generation to generation.

- Contacts:

The International Center Arts of Tahtib - https://www.facebook.com/Tahtib/

Tel. +20 102 406 1481

المركز الدولي لفنون التحطيب Ticfaot - https://www.facebook.com/tahteep/

Modern Tahtib

Address: SEIZA, BAL 66, MDA 14, 22 rue Deparcieux, Paris

Web: http://www.tahtib.com/

Facebook - https://www.facebook.com/ModernTahtibOfficial/

YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/user/tahtibseiza?feature=watch

- Sources of information :

Books:

Al-'Antabri, Farag, al-aalat al-musiqiya al-sha'biya (Popular Musical Instruments). Cairo: Ministry of Media, 1994

Al-Sabbahy, Ahmed, al-maharat wa al-al'aab al-sha'biya (Popular Skills and Games). Cairo: Dar al-kitab al-'araby, 1964

Al-Khadem, Saad, al-raqs al-sha'abi fi Misr (Popular Dance in Egypt), al-maktaba al-thaqafiya series, vol. 286. Cairo: Egyptian General Book Organization, 1972

Boulad, Adel, Modern Tahtib – Egyptian Baton Martial And Festive Art, Budo Editions, 2014

W. Decker, Sports and games of Ancient Egypt, Yale, 1992

D. Farout, Tahtib l’art de l’accomplissement et du bâton, Egypte Afrique & Orient n° 60, janvier 2011, p. 67-69.

Gaber, Samir, atlas al-raqasat al-sha'biya al-misriya (Atlas of Egyptian Popular Dance). Cairo: National Center for Theatre, Music and Popular Art, 2009

Mohasseb, Hossam Eddin, al-tahtib fi al-saeed (Tahtib in Upper Egypt), Annal of the Academy. Cairo: Academy of Popular Art, 2006

Salama, Amin (translation), Encyclopedia of Ancient Egyptian Civilization. Cairo: Egyptian General Book Organization, 2001

Saleh, Maher, al-forousiya wa raqs al-khayyal (Horseback riding and dancing), Magazine of Popular Art, vol. 2. Cairo: Egyptian General Book Organization, 1965

J. A. Wilson, Ceremonial Games of the New Kingdom , JEA 17 (1931), p. 211-220Articles:

Tahtib - https://www.egyptos.net/egyptos/actualite-egypte/le-tahtib-un-art-martial-egyptien-pluri-millenaire-vivant.php

Tahtib and Egyptian Raqs al-Assaya: From Martial Art to Performing Art - http://www.shira.net/about/tahtib.htm

"Tahtib".. Pharaonic Martial Art Turned into a Folk Dance - https://egyptiangeographic.com/en/news/show/376

Tout en baton - https://www.lemonde.fr/sport/article/2014/05/16/le-tahtib-tout-en-baton_4419533_3242.htmlVideo:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OMVHFduY_Eo

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SX0RTJLK4Yo

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=y49gWQWEADg

The Basic Movements of Egyptian Stick Fighting (Tahtib) - https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lj3Zm2TmEVwSource of photos used in this article and gallery:

Photos of International Center For Tahtib

https://www.ancient-origins.net/history-ancient-traditions/tahtib-0015734

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Egyptian_Tahtib.jpg

https://pl.pinterest.com/pin/701154235708765595/

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Tahtib_-AncientEgypt_sport.jpg

https://www.bloodyelbow.com/2019/8/28/20835175/tahtib-egypts-ancient-martial-art-pharaohs-mma-feature

https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tahtib

https://www.hotelsheherazade.com/blog/2017-luxor-national-festival-of-tahtib

https://www.thestar.com.my/lifestyle/culture/2021/05/03/ancient-egypt-martial-art-enthusiasts-eye-olympic-status

https://www.ara.cat/estiu/l-art-marcial-gent-perdia-vida-evolucionat-fins-dansa_130_4454355.html

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Staff_Play_in_Cairo_Street,World%27sColumbian_Exposition_%281893_Chicago,Ill.%29-14595971157.jpg - Gallery:

- Name of sport (game): Testa or Riesy

- Place of practice (continent, state, nation):

Eritrea

- Description:

The Testa (or Riesy) is a fight originating in Eritrea. She is characterized by violent head shots, but her techniques also include kicking, punching, parrying and taking. The hands, feet and clinch grips are very complex and are only used to strike the opponent with the head or the front of the fist (metacarpal head). Biting the opponent in the groin or trachea is something that can also happen in some cases.

- Name of sport (game): Tigel

- Place of practice (continent, state, nation):

Ethiopia

- Sources of information :

Video:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dO7aAlACJu4&fbclid=IwAR19PH_MzPP6C4LMF8Wkj8Yo1mne_Mq6bH7iWvdOY2KviRM9gEk9wGiMxtE

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jfML4QuA6AU

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dO7aAlACJu4

- Name of sport (game): Tiqqar, Thiqar

- Place of practice (continent, state, nation):

Algeria, Kabylie, especially in Tizi Ouzou.

- History:

There was a fighting tradition in Kabylia called Tiqqar ("ruade" in Berber), which meant "hard".

It was a fight in which the young people of Kabylie tested their strength and pain resistance by fighting with their feet. The winner was considered the strongest man in the village and he always had to give a chance to pay back at the behest of the defeated, or else would be ridiculed by all the villagers. These fights were a kind of apprenticeship in the fight for the young.

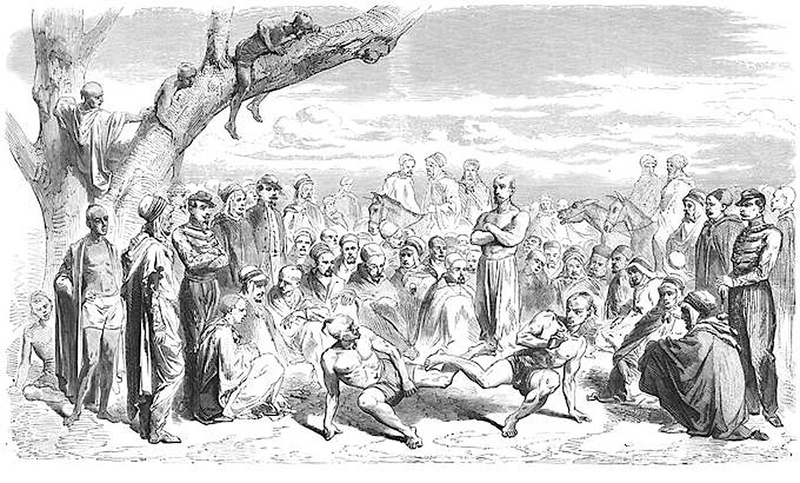

This tradition was still very much alive until the Liberation War in the 1960s, but it began to fade over time. The competition was attended by all the young men of the village, often near the tajmâa (rural meeting place), and was the subject of competition between them individually, as a team, or even between villages. They only used their feet to attack; opponents fight until one of them is defeated, then shout "tuffelt" to end the fight. Each village had its own champions, and often such competitions were held. Tikar ceremony performed for General Nesmes-Desmarets by the Beni Mellikech - La tribu des Ath Mellikech lors d’une partie de Tiqqar, magazine L’illustration, 1857, numéro 769.Source: https://www.oldbookillustrations.com/illustrations/tikar-in-kabylia/

Tikar ceremony performed for General Nesmes-Desmarets by the Beni Mellikech - La tribu des Ath Mellikech lors d’une partie de Tiqqar, magazine L’illustration, 1857, numéro 769.Source: https://www.oldbookillustrations.com/illustrations/tikar-in-kabylia/ - Description:

The opponents agree on the number of players, individually or in teams (1 against 2 or 3 etc.). It may happen that the player himself determines the number of opponents he wants to fight. However, after making a choice, he cannot question it and, in case of failure, takes responsibility for his decisions.

The winner must always accept the challenge of the rematch at the loser's request, even after a very long time, or otherwise be ridiculed.

Rules:

- Competitors only use feet (not knees or hands).

- Attacks are performed while players are face to face, it is forbidden to attack from behind by surprise).

- It is forbidden to attack the head or below the waist.

- The hands may only be used to hold a support (stick, bench, wall etc.)

- In some forms, players may use all available space. In other forms, a circle is drawn within which competitors may not cross, under pain of being eliminated from the competition.

- Players can lock one foot by hitting the other one.Kick techniques:

- kicks with the whole foot,

- heel kicks

- Jumping kicks

- backward heel kicks

- kicks while lying on the stomach.

A fighter's effectiveness depends largely on his strategy. Competitors can look for a fulcrum on a tree, branch or on the opponent himself; The strategy may be to prevent the opponent from finding a fulcrum or finding a fulcrum so as to reduce the opponent's attack field. The players wear a gandour (a kind of light woolen or cotton tunic, with or without sleeves), which allows the blows to be cushioned. However, when clothing interferes with delivering blows, players sometimes hold the fabric with their teeth.

The competition may be stopped at the request of one of the competitors; when either of them is tired, they may ask for a rest and then resume the competition. A contestant may be disqualified when he abuses the allowed stop time or when he is out of range (for example, out of the circle, etc.), when he uses his hand to attack and when he returns to the fight without warning the opponent.

While tiqqar is a great exercise for young people, it can also be a brutal fight when practiced by adult, strong men. - Current status:

Today, this martial art has been somewhat forgotten in Kabylia, but on the initiative of enthusiasts, it is still continued in several countries in a modern form, called Kidokan. Reformed and developed by the master and expert Dr. Mohamed Hamed (died August 7, 2014), the sport is now practiced in 45 countries under the aegis of la Fédération Internationale de Kidokan (IKF).

- Contacts:

Fédération Internationale de Kidokan (IKF)

https://artsmartiaux.page.tl/

E-mail:This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it. Algéria Kidokan Association

https://www.facebook.com/Alg%C3%A9ria-kidokan-contact-association-553232578169504/

- Sources of information :

Source of photos used in this article:: https://www.oldbookillustrations.com/illustrations/tikar-in-kabylia/

- Gallery:

- Name of sport (game): Vététré

- Place of practice (continent, state, nation):

Togo

- History:

It's a game played by the ancestors we played in West Africa when the ancestors came back from the field they are organized in the weekend to be able to play we tried to modernize its purely traditional

- Description:

The Vététré game is practiced by two (02) teams of ten (10) players each including five (05) holders and (O5) substitutes. Each team wears a traditional outfit consisting of one (01) batacali, pants or shorts and a traditional shoe.

- Sources of information :

Source of photos used in this article and gallery: photos by Clovis Mokli

- Gallery: